Photo : Amélie Caron/Radio-Canada

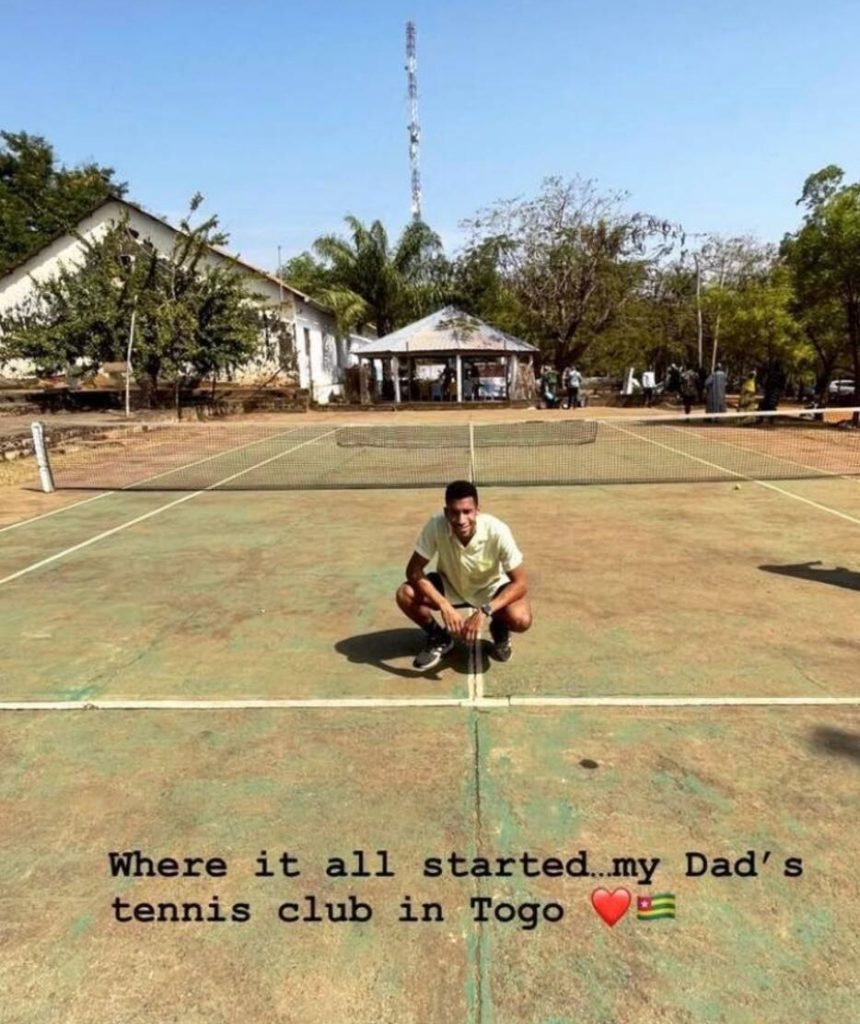

Once upon a time, there was a young man who lived in Togo, a small West African nation flanked by Ghana and Benin.

Like all his friends, the young man wanted to be great on the soccer field, but his coach told him he didn’t play well enough with his left foot.

So the young man turned to tennis.

In the decades since then, Sam Aliassime has passed his love of tennis on to his son—now a card-carrying member of the ATP Top 10—and built an acclaimed tennis academy to hand the torch to so many young players from here and abroad.

Portrait of a father and mentor.

Best foot forward

“In Africa, everyone plays soccer. Every time you see a boy, you see a ball. In my family, we were 11 boys, and because my father ran a hotel with a tennis court, we all played a little tennis. But nothing was more important than that soccer ball,” recalled Sam Aliassime.

“In soccer, I couldn’t dribble or do much with my left foot. I always shot and got passes with my right. My coach said ‘Sam, forget about a career in soccer. You’re not good enough with your left foot.’ I was discouraged, but then I took up tennis full time.”

The rest, as they say, is history. I couldn’t help but ask Sam if he’s ever had the chance to tell the coach how his observation ignited an unbridled passion that helped shape one of the world’s top players.

“I never saw him again,” Sam said with a smile. “If I ever bump into him in Togo, I’ll be happy to let him know and pat him on the back for being honest with me.”

His quick anecdote leads him to another one that’s as amusing as it is interesting. Because everything’s connected.

“A bit like I did in soccer, I had a weakness in tennis: my backhand. When he was very young, Félix realized I didn’t have a good backhand and started beating me. That’s when I began telling him that, if he wanted to play tennis, he had to be good in every aspect of the game. So I put everything in place for him to develop a good backhand. And, oddly enough, when Félix started out at Tennis Canada’s National Training Centre, his backhand was better than his forehand. That didn’t come out of nowhere. It’s from my obsession with my left foot,” he said with a wink.

Read also: Auger-Aliassime Suffers Déjà-Vu with Another Loss to Medvedev

When he was around 18 years old and still a student, Sam was already running his own tennis academy and keen to learn more. “There was no internet to look up tips. So when French cooperants came to Togo on holiday, I’d get a few French tennis magazines with some coaching advice. That’s how I prepared for my lessons.”

Unlike his superstar son, Sam Aliassime never competed in major tournaments.

“Oh no!” he exclaimed. “Even when we played at the national level in Togo, we thought we were very good, but we weren’t. Today, it’s interesting to go back because when I meet players who think they can turn pro, I tell them they have work to do. And that’s what I’m focused on.”

From dream to reality

In many ways, the lack of successful African players is what motivates Sam in the huge undertaking he launched in 2022 in Togo and Côte d’Ivoire to help young Africans remain on the continent instead of having to relocate to make their tennis dreams a reality.

“One day, Félix and I were talking. A lot of players of African origin have been successful in the US, Canada and Europe. Why aren’t there any from the continent? So, I went to see what’s going on—and especially what’s not going on. Everything’s in place, but there’s no structure. I said to myself I’d try to apply over there what I put in place here,” he explained.

It’s what I’ve dubbed the Aliassime Method.

“We have to take the structure here and adapt it to African realities and then set goals for the next ten years. Starting in 2023, we’re going to try and give 1,000 African children between the ages of six and eight the opportunity to start playing tennis within a system to ensure their long-term progress. Whether it’s in tennis or in soccer, the children are naturally skilled, coordinated and athletic. But in terms of strategy, they have everything to learn. There’s work to do.”

Sam Aliassime is focused on people, not infrastructure. Building courts isn’t part of his plan because there are enough courts in Africa. But don’t ask if they’re mostly clay courts.

“I smile because the Fédération Française de Tennis recently sent me a document entitled La Francophonie du Tennis: Réalisations et perspectives [translation: The Francophonie of tennis: achievements and perspectives] about a project it launched in 2021. The federation got in touch with me when it heard about my initiatives in Africa, saying it didn’t know how to make things happen there. I read through it and saw the plan was to build a lot of clay courts. Listen, people are struggling to find drinking water. Forget about clay courts. The maintenance alone is a waste of water,” he said, bringing things back to reality.

Team Africa

Sam Aliassime has enlisted a lot of supporters. He involves the coaches at his academy, the people in his son’s entourage and even, indirectly, Tennis Canada.

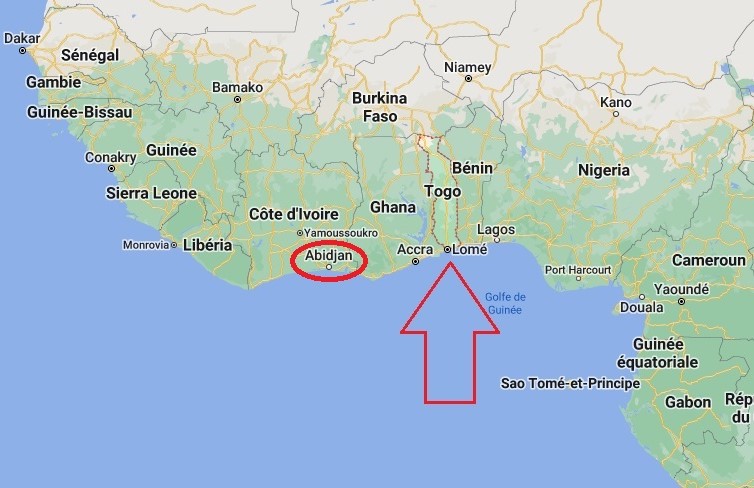

It all started in October 2022 when he travelled to the Ivorian capital of Abidjan to assess about 20 young players from different countries.

“I evaluated them and selected six promising players, five girls and a boy, who started working with coaches and training. But I can’t spend months in Côte d’Ivoire following their progress, so I thought of bringing them here, to Canada,” he explained.

“We filed their visa applications in June. The six kids, who are all around 12 years old, will spend six months training at the Academy to reach a level high enough to play in tournaments at home. They’ll compete for six weeks, return home to their families for a week and then compete again for another six weeks. And they’ll do that for two years.”

When he was in Abidjan last October, Sam was touched by the children’s determination. They’d go up to him and say “Mr. Aliassime, I want to be a champion.” Their words undoubtedly heightened his motivation.

“My dream is to see one of them enter the Top 100 on the junior circuit. They have the potential, they have the heart and they’re hungry. They want to play. It really warmed my heart to see kids who are ready to fight and succeed.”

Read also: The Lost Art of Serve and Volley

It’s currently February 2023. When will a Togolese or an African player join the WTA or ATP world rankings?

“I believe it’ll happen. In ten years.”

Although there’s been very little media coverage surrounding his involvement, Félix Auger-Aliassime has made a tangible financial contribution to his father’s project.

“The selection process cost about 8,000 euros [C$11,500]. I can’t afford that, so he helped out,” Sam told the Journal de Québec newspaper on January 9. He also confirmed that Félix had signed the letters sent to the Canadian embassy to support the young players’ visa applications.

Sam’s daughter Malika handles the administrative side of things. Félix’s coach Frédéric Fontang and physical trainer Nicolas Perrotte will travel to Africa to speak to local players and coaches.

Félix is actually involved in a number of other initiatives in Togo in addition to the African tennis academies. Read more about that here.

Black History Month

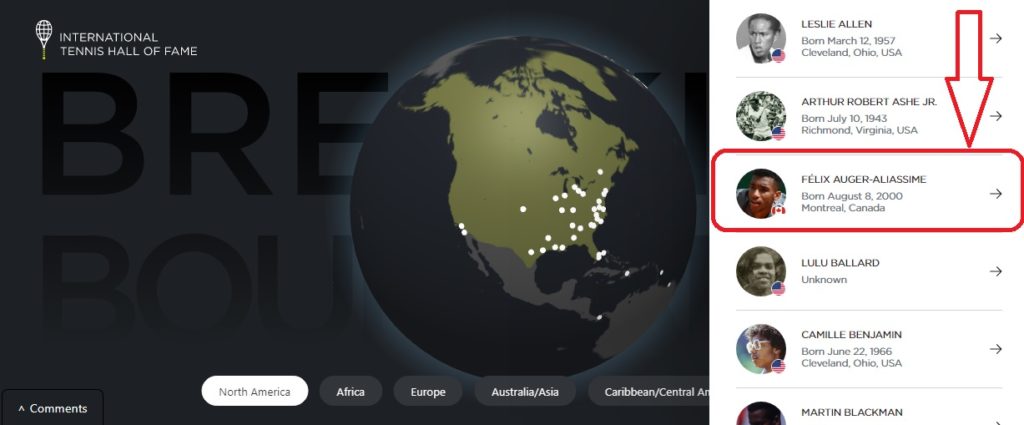

Since last year, Félix Auger-Aliassime has been featured in the Breaking Boundaries in Black Tennis section of the International Tennis Hall of Fame website, which turns a spotlight on players who’ve helped tear down racial barriers in the sport.

While he’s proud that his son has become a world-famous tennis player and role model, Sam is discreet on the subject.

“To be honest, personally, I don’t buy into that very much. Sometimes I wonder if I’m Black or not. In my mind, I’m Canadian, and I don’t see the difference,” he said.

“Over the past two years, I’ve started taking an interest in the issue, and I’ve discussed it with the kids. Can we live without highlighting these events and be equals? Looking back awakens painful memories. Today, if you take a boy like Félix, the way he sees things, he doesn’t say he’s Black. He says he’s Canadian. Personally, I find it veers into something negative all too often. When people ask me if there’s racism here, I never want to get into that because, as a Togolese man who came to Canada, I was welcomed. So I’m not especially interested in that.”

Still, Sam Aliassime acknowledges that things have changed. For the better. And that progress comes with examples.

“When I arrived at this club, here, in Québec, I was the only Black person. Today, there are so many Black kids who play tennis and who believe because they saw Félix do it. And it’s the same in Montréal. There are Black people who get in touch with me, and they’re starting to believe, too. But it doesn’t have to be about Black history. They just need a model, like Tennis Canada has been as one of the most open tennis federations. It put things in place and said ‘Come, you’re Canadian.’ The government and organizations like Tennis Canada demonstrate how open the country is. That’s why Black kids look to Félix. Now, everyone believes. And I can tell you the same goes for coaches.”