Out jogging along the seawall in Vancouver’s Stanley Park, Grant Connell felt disorientated and unable to hold onto his cellphone before tumbling to the ground end over end. When he managed to get himself up onto a bench, his first thought was, “I hope it’s a heart attack.”

Connell, 54 at the time, had been delinquent in taking his high blood pressure medication and knew that a worse self-diagnosis than cardiac arrest would be that he was having a stroke.

It was February 19, 2020, and he was indeed having a stroke. At first, he was hesitant to ask for help because he feared people would think he was drunk.

Fortunately, someone offered to help and he immediately asked them to call 911. Fading in and out of consciousness, he remembers soon hearing a (ambulance) siren and thinking, as he lay on his back on a concrete path, “Oh man I actually have a chance here,” before passing out.

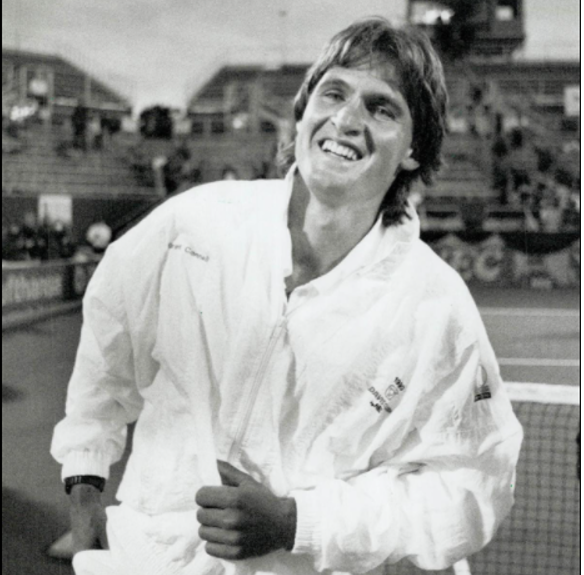

A world-class player who ranked as high as No. 67 in singles, defeated champions such as Ivan Lendl, Jim Courier and Andres Gomez, was No. 1 in the ATP doubles rankings for 17 weeks and played in three Wimbledon doubles finals, Connell was facing a challenge unlike any he encountered in 12 years on the pro tennis tour.

“When I was brought into the ambulance,” he recalls, “I heard them yelling to get a vein and someone shaking me and asking me for my next of kin. Then I blacked out and I think I was out for maybe 12 hours or something.”

When his wife Sarah got to the hospital, the head nurse in the ICU said to her, “listen Mrs. Connell, if your husband wakes up he’ll never walk again.”

His blood pressure was over 200 and initially, medication failed to get it under control. “I heard one nurse say, in the middle of the night when she was looking at my chart, ‘I’ve never seen so much blood pressure medication in one human being in my life,’” he remembers.

After two days the number finally came down. He had regained consciousness and was determined to prove that head nurse wrong. “I never thought that I wasn’t going to be able to walk,” he says. “It was really difficult to learn how to do it again – but that was something I never considered.”

Today, two years later, he walks with a limp and still has very limited use of his left-side (he’s a lefty) arm and hand.

But more than any physical ails, Connell’s first reaction upon coming to in that bed at the Vancouver General Hospital was recognizing that his mental and emotional faculties were still intact.

“I was happy that I could understand people and that they could understand me and that my brain was still functioning well, my memory was good,” he says. “I had done research on stroke (there’s also a family history) and did know that you could go blind – my left eye is damaged (24 per cent vision) so I can’t drive. But if the blood is on top of your brain – as opposed to mine which was an inner-cranial brain bleed – if it’s on top, that’s when it really fries your connections and you’re done.”

Connell was far from done and, after a month in the hospital, he was transferred to a rehab residence and was not able to return home for another three months until the end of May.

His recovery has been slow and laboured but today he goes for five to 10-kilometre walks and has been back working in his Vancouver realty business since six months after the stroke.

“Realtors are independent contractors anyway,” Connell says about his job. “I’ve been in the business for 20 years and I’ve actually had a pretty successful two years now.”

With characteristic Connell mischievous humour, he adds, “I tend to call it a handi-perks. The perks of being handicapped. I might be getting a bit more business than I normally would. It gets me out. I Uber a lot, and I’m not averse to taking the bus.”

During his career, a highlight was almost singlehandedly lifting Canada to the World Group of Davis Cup for the first time by winning all nine sets – two singles and the doubles with Glenn Michibata – against the Netherlands (Paul Haarhuis and Mark Koevermans) on a memorable, cold, late-September weekend in 1990 at the National Tennis Centre in Toronto (picture below).

After retiring in 1997, Connell was executive director of Tennis British Columbia from 1998-2003, Davis Cup captain from 2001 to 2004 and tournament director of the Canadian Open (Rogers Cup) in Toronto in 2006, all the while starting a work-life away from the sport. “I can never complain about being overlooked when they talk about Canadian tennis players because I really took myself out of it,” he says, “purposely went on trying to find myself outside of tennis – with a family and then a career. I was never one of these guys who likes to look back. I like to look forward.”

He remains in close touch with tennis contemporaries and many of them rallied around him when he had the stroke. “There’s a WhatsApp group called ‘Grant’s tennis friends’ that (former doubles partner from Tacoma, Washington) Patrick Galbraith set up. There are about 30 of us from the tour when I played – guys like Glenn Michibata, Todd Martin, (Jonathan) Stark, (Byron) Black and (Patrick) Rafter – just us going back and forth every few weeks.

“When I was in the hospital, I was on it every day chatting with people. The international tennis community was incredible.”

There’s one tennis memory that many Connell followers have from his career – a 4-6, 6-1, 6-7(6), 7-5, 6-3 loss to Andre Agassi in the first round at Wimbledon in 1991. Agassi had a net-cord ball trickle over for him facing a break point that would have allowed Connell to serve for the match in the next game. Agassi went on to reach the quarter-finals. But had Connell won the match, it’s doubtful the American, a Wimbledon grass skeptic with a match record there of 0-1 at the time, would have had the confidence to make a career-changing breakthrough and win the title the following year.

“He (Agassi) wrote about that in his book (‘OPEN’) and I laugh because I got more attention from two lines in the book than I did in my whole career,” Connell says. “I was in Hawaii with some friends when that book came out. Everyone was reading it and I jokingly said, ‘I could put a marker in my hand and open to the page and just sign it and close it.’”

It reminded him of another Agassi story – from 1990 when he lost 6-4, 6-2, 6-2 to the flamboyant Las Vegan in the first round of the US Open. Recalls the self-deprecating Connell, “(The late) Vitas Gerulaitis, when I was playing Agassi at the US Open, said, ‘this is like watching the tortoise and the hare – and the tortoise doesn’t win.’”

In so many ways Connell has won – particularly with his family. Daughter Madison, 23, graduated from Stanford and now works in San Francisco, daughter Charlotte, 19, is currently studying at McGill in Montreal and son Cooper (his Bermudian mother’s maiden name), 20, is at Bentley University in Waltham, Mass. near Boston, on a hockey scholarship studying business. His two youngest – 15-year-old identical twins Bella and Katie – are in grade 10 in West Vancouver.

Connell, wife Sarah and the five kids went to Wimbledon in 2019 (picture at top) and, in Connell’s words, “had so much fun.”

He couldn’t help himself, joking, “it was funny watching my underage kids drinking Pimms (the gin-based liqueur synonymous with Wimbledon) with their friends.”

Son Cooper turns 21 in July and Connell plans to go to this year’s US Open with him to celebrate.

Back to his current physical reality, Connell says, “I’m quite limited. I can mow the lawn quite gingerly but I don’t have the balance to play tennis or things like that. I don’t rule it out – it’s been two years. They tell you to grind away for a couple of years and then do whatever you like sort of thing. I have the greatest physio and I go three days a week and I’m seeing incremental improvement in my hand and my arm. So it gives me reason to believe I can get 10 per cent, 15 per cent, 20 per cent better.”

Grant Connell – tennis player and all-around good guy – was captured in these final paragraphs from a September, 1997, column in The Globe and Mail on the occasion of his retirement.

Connell’s wit and irreverence are his calling cards, and a good example is when he received his doubles runners-up prize in the Royal Box from the Duchess of Kent at Wimbledon in 1993. That year – memorable for Jana Novotna sobbing on the Duchess’s shoulder after blowing a third-set lead in the women’s final against Steffi Graf – Connell had a little chat with the Duchess. “She was very personable and friendly,” he recalled. “So I turned to her and said, ‘Don’t worry, I won’t cry on your shoulder.’ She smiled and said, ‘Oh thank you, I hope not.’”

From the corps of retired gents who worked as volunteer drivers during the Davis Cup (Ed. Note: September, 1997, in Montreal) and who gathered around Connell as though he was one of their old pals, to the woman who arranges player interviews at Wimbledon and who recently remarked, “Grant Connell, he’s our favourite,” the 31-year-old from Vancouver has legions of admirers.

One of those is long-time friend and former fellow-player Martin Laurendeau from Montreal. “I have the most amazing wife and five kids and friends and community here,” Connell says. “I saw Marty the other day and we had great laughs. I think I put people at ease pretty quickly because I can joke about things. And honestly, through this whole process, it’s been alright. I’m so, so lucky that I woke up happy and grateful, unbelievably grateful – more in love with my wife and kids than ever before. The blood could have manifested itself in many different ways. And when I was at the rehab hospital I saw many people with similar strokes and they were absolutely miserable. I was just so lucky in where the blood landed that it didn’t affect my moods or my outlook on life or anything like that – if anything it enhanced my gratitude for life.”