Photo: Lawrence Industries

Year after year, for one month only, the most unusual and rare form of the game is played: grass-court tennis.

The fleeting interlude culminates in the third major of the year, in London’s SW19 postcode.

Way back in the 19th century, the surface hosted the very first matches of the sport we’re familiar with today but has since come to embody nothing more than the remnants of its former glory. Indeed, only tradition keeps the grass green. And, as you know, tradition has an important place in the hearts of fans, so don’t expect to see the end of grass-court tennis any time soon.

One would imagine that hosting what’s said to be the most prestigious of all the Slams must require a pretty extensive landscaping department.

Maintained and manicured

Piloting this essential service is William Brierley. The prominence of the courts he upkeeps has made him a well-known figure in English tennis circles. There is such vested interest in his work that the senior groundsperson connects with fans around the world and is prepared to answer all their questions on his beloved blades.

He’ll tell you that the lawns are seeded with ryegrass, which has the advantage of appearing quickly, in less than a week, and growing just as fast, so the weather and all its unpredictability doesn’t get the upper hand. That’s a good thing considering the treatment the 18 Championships courts and 20 practice courts suffer before and during the tournament.

Another feature of the ryegrass, which is made up of three cultivars, is that it yields a better bounce.

In the four months leading up to the Slam, systematic mowing based on the weather conditions cuts the blades, millimetre by millimetre. From 13 millimetres in March, the grass is trimmed to 8 millimetres at the start of the tournament—a length that was established in 1995 and has remained unchanged.

Every morning, groundspersons clip the courts using Toro cylinder mowers. The surfaces are marked by a machine that puts down titanium dioxide for the lines, which are 50 millimetres wide and 100 millimetres at the baseline. About 2,275 litres of the pigment are used every year.

Rufus the Hawk

Finally, to ward off any pigeons that may be tempted to spoil all the hard work and peck at the treasured sod, Wimbledon doubles down on prevention and protection with Rufus the Hawk, who watches over the precious emerald lawns (precious from the affective and financial perspectives, of course).

Rufus the bird scarer is a Harris’s hawk that made his debut in 2000, at a time when winged intruders were a constant concern owing not only to their appetite for the seeds but also to the disturbances they could cause during matches.

With its celebrity status, the bird caused quite a stir in 2012 when it disappeared. Likely abducted and freed soon after, Rufus was found in a nearby park to the huge relief of tournament organizers and got right back to work.

Rufus happens to have his very own credentials, which you can catch a glimpse of in this gem entitled Rufus – The Real Hawk-Eye in a nod to the electronic line calling system. Produced in 2014, the video is part of Wimbledon’s Perfectionist series of promo videos.

As you can see, the Wimbledon details—and I only covered a few of them—are quite fascinating. For more, head over to Forbes to read Wimbledon: Caring for the World’s Most Famous Lawn, which I used to research this piece.

Rain delay

On the first Monday of the tournament, I turned on my TV to watch Rebecca Marino’s opening match, which came to a halt in the 10th game of the first set when rain fell for the second time. When the slightest drop hits the grass, the safety of the athletes comes first, and the players are whisked away immediately—unlike what happens on the hard courts and especially the clay courts, where play goes on for much longer despite the mist.

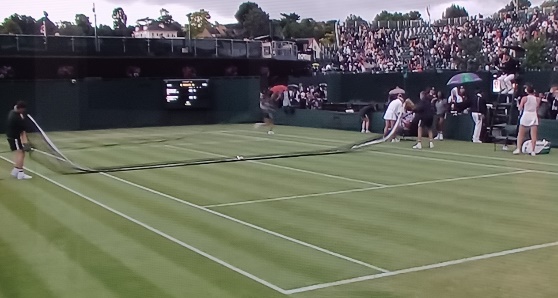

While the commentators discussed the situation, the work of the groundskeepers was on full display.

As soon as the net was taken down, attendants ran long straps across the width of the court to unroll a large waterproof canvas (the straps were later used to re-roll the cover after the rain). Once spread, the tarp was lifted and shaken for perfect coverage.

It was just over two minutes—2:20 to be exact—from the time the umpire stopped the match to the time the court was fully protected.

It was as fun as it was interesting to witness the organization, discipline and precision of everyone’s movements, complete with orders and encouragement from the on-court supervisors.

And it happened simultaneously on 15 of the 18 Championships courts that don’t have a roof.

Efficient, indeed!

How much longer?

As I noted earlier, it’s more out of respect for tradition than necessity or pleasure that professional tennis continues to spend a month on the grass courts of the Netherlands, Germany and England.

Will tennis ever be played on a single surface, like all other sports? Or will the tradition of different surfaces continue, even if only for one month out of the year? We’ll see.

While some players, like our very own Félix Auger-Aliassime, adapt well to the grass, others immediately frown when the topic is brought up.

As I wrote last year in this blog, there are many athletes who would gladly do without the layover on grass, an ephemeral surface that begins to break down on day one and can get to be patchy and even dangerous.

I’ve already shared my opinion right here.

Email: privard@tenniscanada.com

Twitter: @paul6rivard

Follow all our Canadians in action here.